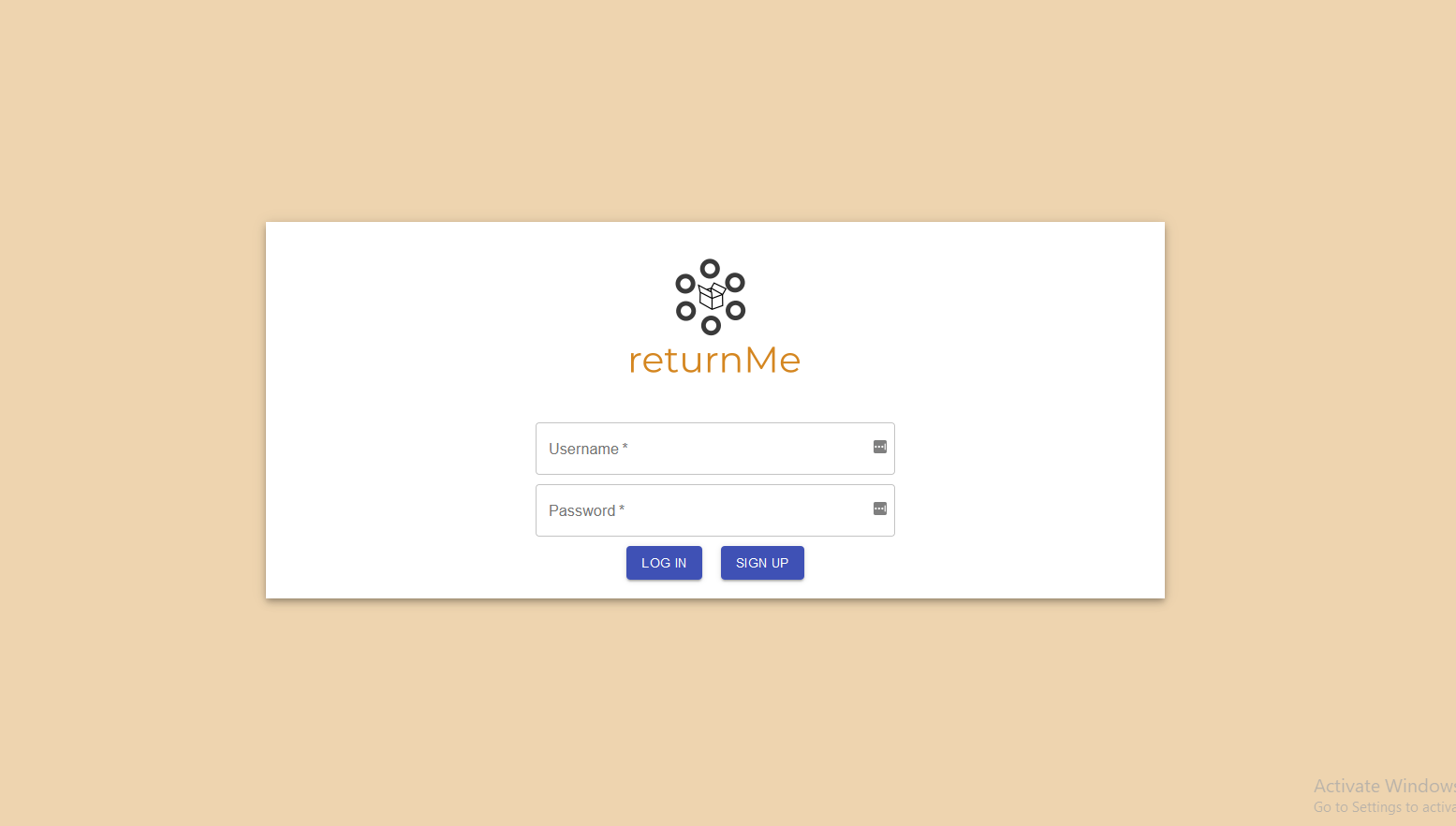

ReturnMe

tl;dr: Young immigrant entrepreneur created a returns pickup service that disrupts the industry! Source | Demo

Car culture in America is pretty strong and Boston isn’t much different. Although Boston’s public system isn’t bad, it isn’t all that great either. Most of the train lines are centred around the main city centre and makes getting from one point outside of the city to another point extremely tedious - a 15minute drive could easily be an hour commute requiring a combination of train+bus+walking.

As a result, doing package returns can be pretty tough which got me thinking: What if a service solely focused on package pickups existed? Yeah sure, package delivery services already provide this option, but they can get pretty expensive and are normally pretty hit or miss. I’m talking about a flat fee service that’s consistently ontime that picks up any package, regardless of provider. A quick Google search shows nothing quite like this exists yet. So, I made my dreams come true and coded out a prototype myself.

The Code

As always, the source is pretty expansive and I’m only going to write about the interesting bits in this post. The stack that I chose to use for the server was Node Express + Typescript + MongoDB + Mongoose. Using Mongoose with Typescript took a little finesse to get working properly and cleanly together, but we’ll get to that in a minute. As for the front end, we have Typescript + React and everything’s packaged together nicely using Webpack.

The Server

The server is just a really simple REST API. One trick that I’ve learned online was that when thinking about names for REST endpoints, try to use nouns instead of verbs. Aside from the user verification portions of the project, the rest of the endpoints adhere to this rule pretty well. In terms of software design, to keep things (relatively) neat in my main endpoint file, I’d delegate the main logic to a Controller class. This way I could just tell the relevant Controller to do the work and return when it’s done.

class Controller {

...

public async createReturn(inReturn: IReturn): Promise<IReturn> {

//Make new IReturn object

const obj: IReturn = new this.Returns({ ...inReturn })

//save it to model

const result:IReturn = await obj.save();

this.db.close();

return result

}

...

}

//Creates a new return from a user

app.put('/api/returns/user/:userId', async (inRequest: Request, inResponse: Response) => {

const controller: returnsController.Controller = new returnsController.Controller();

const confirmationNumber: IReturn = await controller.createReturn(inRequest.body);

inResponse.send(confirmationNumber._id);

})

I’ve got two main controllers for each separate database: a returns database to hold information about a user’s returns, and a user database that holds usernames and password for the user. This brings me to the next part: using Mongoose with Typescript

Schemas & Models

Coming from a formal relational database background, the thought of not having a proper schema made me a little scared. For this project, I chose to stick with something a little closer to what I knew, and tried to add a schema to the database. To keep things neat, I decided to keep my schemas in a separate folder. The trick here is to define an interface which extends a Mongoose Document and use that as a template argument to a Schema:

export interface IUser extends Document{

username: string,

password: string,

name: string,

}

export const UserSchema: Schema<IUser> = new Schema<IUser> ({

username: {type: String, required: true},

password: {type: String, required: true},

name: {type: String, required: false},

})

Later on, I instantiate use the schema to instantiate a model like so:

this.Users = mongoose.models["users"] || this.db.model<IUser>("users", UserSchema)

Using a schema helped me keep track of things in my head and link it to what I’ve learned from school. With that said, I aim to experiment with pure Mongo in the future. I’ve looked through the pros and cons after reflecting this project and I can definitely relate to the cons associated with trying to define a schema at the early stages of a project: you can’t. There are a lot of changes/redesigns that occur when you’re creating something which kind defeats the purpose of having “loose” database keys that you can change with ease.

Passport.js & Authentication

One thing that was actually pretty cool about this project was doing the user authentication from scratch. To do this, I used Passport.js. It’s relatively lightweight but the documentation wasn’t too extensive when it came to writing your own username/password authentication. Luckily I found an unofficial documentation here.

Before we tell Express to use Passport, we need to tell Passport to use a custom strategy

passport.use(new Strategy(

function (username, password, done) {

//Hand off to UserController

const controller: userController.Controller = new userController.Controller();

controller.verify(username, password).then((user) => {

console.log("Login Success")

return done(null, user)

}).catch((err: Error) => {

return done(null, false, { message: err.message });

})

}));

//Then we tell Express to use passport

app.use(passport.initialize());

app.use(passport.session());

Once that’s done, we need to define a couple of functions in order to get everything wired up correctly. In order to use sessions and have the browser “remember” a user, we need to overload serializeUser and deserializeUser on the passport library to take in your custom users as arguments

passport.serializeUser(function (user: ISerializedUser, done) {

done(null, user.id);

});

passport.deserializeUser(function (id: string, done: (err: any, user?: ISerializedUser) => void): void {

const controller: userController.Controller = new userController.Controller();

controller.getUserById(id).then((user) => {

const deserializedUser: ISerializedUser = {id: user.id}

done(null, deserializedUser);

}).catch((err) => {

console.log(err.message)

done(err);

});

});

The serializeUser function just calls the done function and supplies the verified userId while the deserializedUser function takes the given id and passes it into the supplied done function. To be honest, I’m not really quite sure what the done function is, but hey it works.

The Client

With all the backend stuff out of the way, we can finally start building a sick frontend. But hold up with all the hooplah we wanna keep the code clean. To do this, I created largley followed the same design for my backend. I really wanted to separate the React code from the regular code that communicates with the backend. So I had Controllers to do the main logic and REST API calls, while I kept my react components in a cute little components/ folder.

The src/ directory structure looks like:

src/

| components/

| | |someComponent.tsx

| someController.ts

In someController.ts:

export class Controller {

public async login(username: string, password: string): Promise<boolean> {

const data = {

username: username,

password: password

}

return axios.post("/api/login", data).then((res: AxiosResponse<string>) => {

return true

}).catch((err: AxiosError<string>) => {

return false

})

}

...

In someComponent.tsx:

const App: React.FC = () => {

//Some fields/states

...

//Tell Controller to make the requests...

const submitForm = async (username: string, password: string): Promise<boolean> => {

const loginWorker: Controller = new Controller();

const isAuthenticated = await loginWorker.login(username, password);

if (isAuthenticated) {

const userId: string = await loginWorker.getUser()

setIsAuthenticated(isAuthenticated)

setUserId(userId)

return true

}

return false

}

...

return (

//some rendering logic

)

As you can see, the .tsx file doesn’t hold any info about the API endpoints, and all the API calls and error handling etc. are done in the .ts file.

Aside from that, there really wasn’t all that interesting going on on the frontend. It was kinda standard React things, no real animations or anything fancy and pretty standard stuff. I did build a landing page, but I don’t really have an eye for frontend design and I just kinda rolled with it.

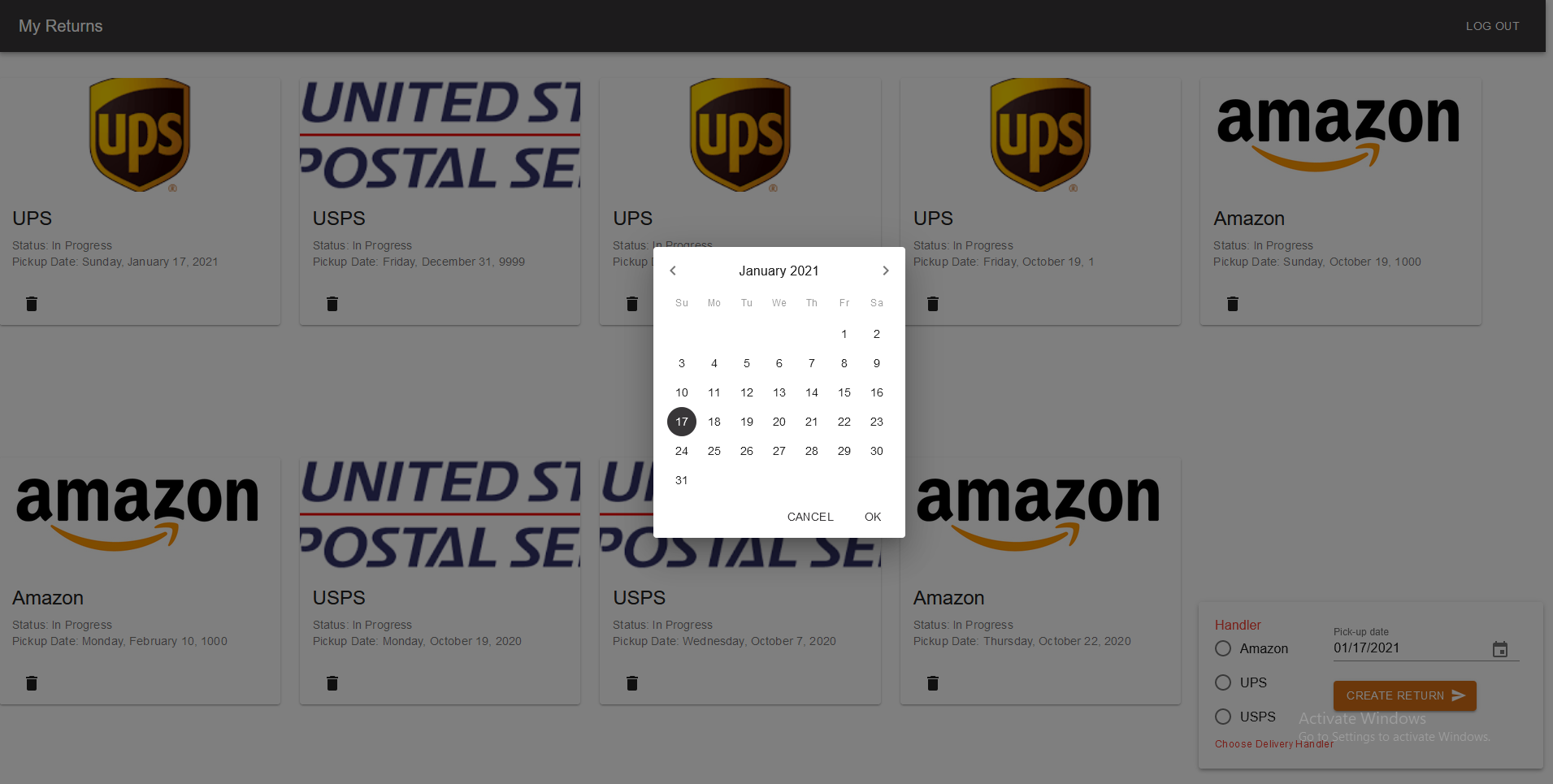

My thoughts

My main goal for this project was to just take an idea and run with it. Yes, I could have built more features like added in an interactive map to track the locations of a delivery etc. but eh, the minimum proof of concept was done. I think I learned a decent amount with this. It was time to call it done and move on to my next project: a CHIP-8 emulator!

I really enjoyed working with React (it wasn’t my first rodeo) and making a fullstack project from scratch, but I really enjoyed solving problems about why a function isn’t spitting out the right output, or why am I not getting data that I want etc. Switching contexts from frontend to backend was also really expensive when I was writing this, and I can say that I had a lot more fun building the emulator, BitTorrent Client and the C++ synthesizer. Oh well, I did learn a bunch and can definitely say I had some fun working inon this. Who knows, maybe some VC will stumble upon this and offer an acquisition!

The Final Product